1. The First Gathering

Our first session was an intimate one. Considering the fact that it’s been a good while since I actually sat with people who were not my close friends and family or hiding a good half of their face behind a mask, it was even more joyful.

The organisation part and introductions aside, we talked about the book cover, which is a photograph of the installation “Double-Doors II, A+B”, 2006/2007 by Rachel Whiteread. We talked about doors as façades – implying that there is a way forward, a way out. Yet all is waiting for you behind them is a wall, or better yet, another door. Leading to another door. Hoping, waiting for you to give up, to turn around. To stop trying.

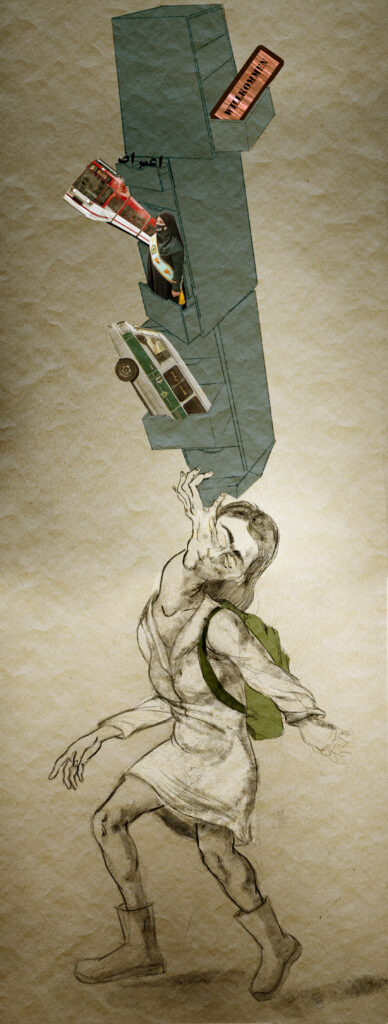

It reminds me of a Polygon article I read a good while ago about the video game Bioshock: Infinite. I can’t remember much of the article – but I remember that somewhere I stumbled upon this John Scalzi quote: „Being a straight white man is playing life at the lowest difficulty setting there is.” I liked this quote, I still do, it sounds smart. Difficulty settings of life as the difficulty setting of a video game. I’d argue that the same applies to our topic, winning the game of getting through the doors. Doors will be bigger, taller, more intimidating the further you get from being an able bodied cis straight white man. And you’ll be carrying more than your own weight (and your paperwork) with you. All the things that you had to overcome, to prove, as a woman wanting to exist anywhere other than under your own roof, inside your own walls, behind a door. The very first door separating you from the world outside, from fresh air.

This is a concept that I know too well as a woman coming from the middle east (which is not a good start to anything) and from a highly religious, patriarchal and misogynistic society. The first thing you learn as a little girl in my country is that the world outside is not safe. The streets, oh specially the streets at night but streets in general – metro underpasses, university, workplace, your boss’s office – definitely not safe. Your boyfriend’s home? God no. ANYONE’S HOME – say, a co-worker you have to shortly meet to hand them some documents, an artist who is holding classes in their home – oh, dear, you’re so looking for trouble if you go there.

Just being in these places means you deserve whatever happens to you. That’s what we learn. Some hear it from others, worried moms, super-worried grandparents. Or you read someone’s experience on the internet. Then another one. then another. You hear it from a friend of a friend who had to run away from a driving car catcalling her and asking help from a police officer, only to be asked why she’s out so late at night looking like this. Your friend gets abused by her boss who had asked her to stop by his place to grab some files. Your friend is not going to tell anyone. No going to file a complaint. She knows too well where that door is going to lead. A few other doors, surly, to get her all warmed up, and a pretty good amount of victim blaming. Oh, and losing a job.

She learnt it as a little girl. And, she knows, as I do, and all the women in my country – you are not safe outside. So, anything that happens to you after you close your home’s door behind you is your own fault. You were asking for it. You had it coming.

And well, what if a woman is assaulted inside her own house? Glad you asked: what happens behind closed doors stays behind closed doors. Private family matters, right? People argue. Husbands beat up their wives, fathers cut their daughters’ throats, brothers lock their sisters inside1. Such is life.

Thinking of a door as something which is separating your (if you’re lucky) safe space from the world outside led me to another interpretation of the picture of the doors without locks, without handles: you can’t keep anyone out. Assault – be it sexual, physical or verbal – is indeed nothing but an invasion of a personal space. A door without a lock can’t keep anyone outside, it can’t keep you safe.

2. The Book Launch

The online book launch took place exactly after our first session. I missed my bus and had to walk an unpleasantly long distance in the dark, while listening to Sara Ahmed and other women who had one way or another contributed to the book. Some of the women whose “testimonies’’, as Ahmed calls them, were used in the book came to word, and I was humbled by their courage and inspired by their strength to show where it hurts, to show vulnerability. I imagine every time you retell a story of experiencing abuse you are reliving it, opening the wounds again and again. Questioning your actions and doubting if you did something wrong, if you – typical in where I come from, as I mentioned – had it coming. I found myself envying those women – which does not sound right. But later as I talked about the event with a friend – also from my country – she said she felt it too. A sudden burst of loneliness hit us, as we realised how much we want to hear the same discourse in our mother language. How out of reach it still appears and how high the price of that could be.

Which brings me to another powerful aspect of the event, and the book, and the whole concept of a „feminist collective”: we are, in fact, not alone. Now, it doesn’t magically take the pain and the frustration away. But there is something empowering and comforting in knowing that. And the more people join the feminist collective the more powerful we are. We have even experienced it with Iran’s meto movement too, which has gained momentum in recent years. Women started talking, complaining, out loud, without censoring themselves, and about men, which is as horrifying as a woman can get – in the eyes of the abusers and their apologists. Big names were outed by the women who suffered harassment, especially in the art field2, and then many others got the courage to talk about past or ongoing traumas caused by co-workers, bosses, professors, friends, and family members.

I had all these in my mind, listening to the bittersweet event. And that’s when I heard yet another interpretation of doors from one of the participants, my favourite one: doors are not always there to frustrate and disappoint, she believes. Sometimes you open a door and there’s a whole feminist collective waiting for you behind it.

Growing, and empowering.

- I am of course talking about the so-called honour killing and its long tradition in my country, which is beyond the scope of this post.

- I do not think that anyone should draw the conclusion that for whatever reason, men who are active in the art field are more likely to commit harassment. I further believe it’s the women who play an active role here. Studying art in general is not something that most traditional families in my country would welcome, it doesn’t pay much and people involved are hippies and addicts and corrupted, so they say. For a young girl to get into the arts, especially cinema, requires a good amount of courage to begin with. Hence they are more likely not to remain silent in the face of abuse.