“I’m not going to complain today, because I have wonderful people surrounding me”

14.01.22

“I’m not going to complain today, because I have wonderful people surrounding me”

14.01.22

The summary was urging to be done and therefore, we are coming back to the roots: the place where the complaints were planted, watered, and let out by the complainer-creator, to the #0.

I do wonder sometimes why I have started voicing the itchiness I encountered. The following question would be why I do art. Then again, after rereading the displeasures once in a while I always bump into the satisfying answer. Moreover, I love my army of complaints. The question would pop up: how is it possible to have an emotional connection to the displeasure? I might not be able to explain it well, but assume that for me it comes from the joy of complaining, the power of reflecting, something very personal, one-man therapy, the empathy with the protagonists of my story, and most importantly, being able to be vulnerable somewhere, more than anywhere else. The topics that I touched through my displeasures are a good base to realize what are the itchy places and triggers, more precisely the base for future complaints and that is, my complainers, what I was looking for a while. I might be my own feminist ear.

Is it, now when I opened these very personal, but very public questions and realized how sticky they are? Now, when I am aware of the damage that has been made? It can not be more of destruction than actually taking the words and bringing them into action. I and my displeasures are already here, which is, as I experienced, definitely not enough. Otherwise, Ahmed would call it a fatalist process (opened and started just in order to be initiated). But I would say that if my voices are burning now, there must be the next stage. Therefore, let me complete this action until it gets visible.

After voicing displeasure #The Code of Visibility, I could finally cry my life off, after months of holding it back. The wonderful moment of being able to tell him how hurt I was is not the pathetic story about my father, as I always thought. It is the voice of all the girls in the world that were abandoned, living with the thought that they made a mistake. It is the voice of the anger, the spit of the tension that pierced my belly for years. Thinking about the children that are very present in my everyday life, I pictured the visibility that their complaints are creating: the contrast of being taken too seriously, or not at all. I have been observing both their creation of visibility and complaining in front of the authorities and I actually found something useful to apply in my own practice.

Never mentioned before that I have always been disguised and repelled by the way my family structure is described in the official documents. It gave many people the right to comment and construct their own perceptions of the two members of my nuclear family. I hated the way they victimized my mom seeing her as a tortured, poor woman, the single parent left alone. Once, in the report of a school psychologist, she wrote: the child’s lack of motivation due to the consequences of her broken family. Whatever would change in my behavior, that was considered weird, it was always attributed to the crack I was born in.

Once, I cried in front of a 5 years old girl I babysat because her toy/doll family construction matched mine very well. Instead of stopping the professional cry, I started the professional complaint in front of her and the game was successful. The feminist ear has no gender and no age.

voicing the burning

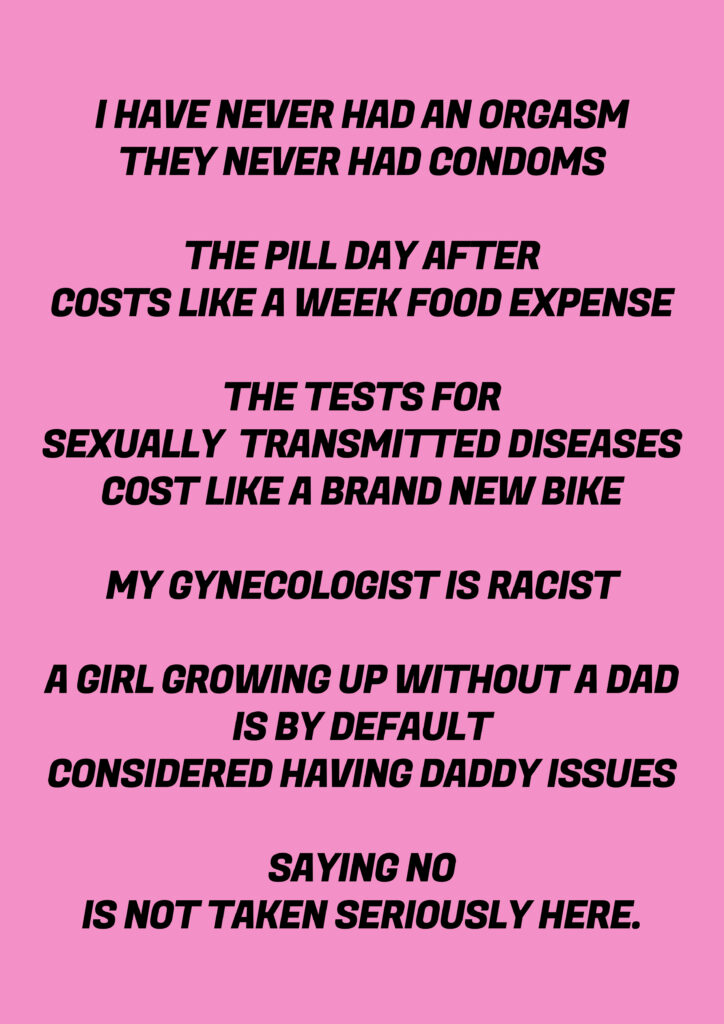

#The Professional Cry is a fusion that gravitates and connects displeasures written before and after it. It is, indeed very much connected to the first displeasure #Feminine Masculinity. Both empowered my female/male voice and helped me understand the NO complaint. I was not respecting my own body, and my own little girl cried inside me every time I gave it to them. I was sexually harassed, taken advantage of. I experienced verbal abuse not knowing that what has been happening is wrong. I never told that to anyone, because they would immediately give credit to the broken family situation: seeking love more than others, daddy issues, loneliness, not having a man figure to look after, etc. I am not saying that traces of the crack are not present, but how dare you? Developing masculine femininity is a process and I prefer saying that my deep voice is therefore a social construct.

This must be a professional crying class, voicing up and healing the cracks.

#The Crying Honk was, on the other hand, at the beginning very general, global, touching something outside of my body. I started writing it after the second day of my trip to Egypt thinking about the reflection on the way. After a while, it became strongly personal and I noticed that this was the task of mine, the one this life urges me to have: I am the voice of the children. I always felt this whisper more than others and whatever is the context, I ended up working with kids. At least I know whom I inherited this complaining skill from. Therefore, the more honest and radical I was, the more visible I became. This might also be called radical softness because my words are written faster than my brain can check them. I am simply unloading and emptying my cabinets within each letter.

So, how to treat these empty pieces of furniture that are piling up? How to fold all these tears and screams-soaked napkins? Where to store them? The collection of the voices, cabinets of displeasure, university of ears, feminist laboratory, collective hug, complaining choir – (some)where to go?

I have a trillion questions while burning on my own and some of them are adding oil on fire, while some are swallowing me even more into the topic. I am asking:

What is the difference between psychotherapy (type of a feminist ear), official complaint (including administrative process e.g), and art practice here, for me? What am I proposing and voicing? What would happen when the voices are heard and the cabinet is exposed, becoming visible? Will my writings hug the people, motivate them? What do the complainers need? Is it more of the introspection and individual complaining experiences or the instruction of how to make an act?

Will anything voiced drastically change anything existing?

Until all of them are answered,

until it all burns.

The sound of collective praying made me tremble. I heard the voice coming from the top of Ibn Tulun mosque communicating with the other voices, the choir of Al-Qāhirah. The collective vibration transmitted through the architecture gave birth to a sobbing city I had a chance to encounter.

Why are you crying? ارجوك لا تبكي.

Scared for my white skin, I walk through the dusty bubble and pray for my white skin not to get dirty. For my white skin not to get raped. For my white skin not to experience poverty. My privileged, white body prays for the kids from this street, for the mango traders of Bazar, and the mothers feeding their newborns on the pedestrian zones, beyond the legs of passengers. The white privilege that I have not chosen but was given to me. With the whiteness and ability to wash my face after a long day on the streets, I dare to ask: how can we be part of the same planet? Me and this little girl in front of me, being alone on the street? We, small humans spreading inequality. We, mute humans, do not hear the cry.

On day 4, I slowly accepted these scenes as a part of the landscape and got used to poverty.

Being loud or visible has many purposes: from the simple joy of having attention to the emergency blankets, danger alert, and simple, everyday fear. I find the ambivalence of the honking orchestra here being disturbing and meditative simultaneously. The sound of confirming the presence on the road. Another form of crying, right? Traffic tears, polluted breath, screaming brakes.

Somehow, this typical Egyptian honking practice sounds very much like my own cry – hysteria, anger, the language of the unique emotions. Imagine honking as the only voice you can use. The honking makes you want to explode in your own anxiety and drown in your own tears. Or in mine, if you wish.

“The relationship between Occident and Orient is a relationship of power, of domination, of varying degrees of a complex hegemony.”

Said, Edward W. 2003. Orientalism

The postcolonial studies introduced us to the Westerns depicting the Orient as an irrational, strange, weak, feminized “Other”, contrasted with the rational, familiar, strong, masculine West. I would gladly comment on something that opposes the otherness, the one belonging to Orient (from the previous view), and reflect on my own, Occident otherness experience in Egypt. It is very important to underline my position here: I am not a scientific researcher on the topic, nor competent to discuss postcolonialism on any deeper level. The fact that these were my first steps out of Europe and the ways I used to experience each of them urged this reflection and made it very personal.

As I have already voiced in one of my displeasures, it feels that my everyday purpose is to be visible wherever I am and no matter what I do, say, or behave, my visibility was never so present (I dare to say even successful visibility in my case) like here. It is not me, Nadja, being exotic otherness in Egyptians eyes, but us, Nadjas that came to enjoy the heritage of their country and leave a few pounds more, possibly. And here I was even more white and prestigious, being considered a German within the group of German students I came with. What fascinates me among many things here is the way of communication that consists (besides the honking) of a couple of questions as where are you from; what is your name; and multiple versions of welcome to Egypt. These questions are never meant to actually be responded to, but to deepen the conversation, lead to the possible trade, and give them ”the promise”. Each word answering their conversation starter is a permission to enter the platonic friendship where you are the one promising to buy, to sit there and, necessary, come again. Such intensity in everything happenings. Welcome, to Cairo, they said.

What is your name?

My name is Nađa, that, according to Russians comes from Nadezhda (Надя) meaning hope. According to Arabs comes from Arabic Nadia (Nadiya) meaning moist; tender; delicate. One of the sellers from Bazar told me that the meaning is a short, but very fast river. I wanted to run aweay, that's true.

So, you are Egyptian? I was asked.

The first time in this symbolic 25 years I exist in this world, somebody took the picture of me because I was different than everybody else there. I was the exotic, fascinating alien among the ordinary, everyday man on this continent. Instead of giving the superiority that attention usually does, I felt the opposite. I felt small and different in front of the whole world that I had no idea about. I felt the heaviness of the cloak of otherness that was worn by the people of color in Europe, Muslims praying on the street of the Orthodox country I came from, the women with hijabs, etc. Their unusual, extraordinary behavior or look was taking the attention of ”normal” white people and now, it is was me: an alluring, foreign subject.

I would revive the Serbian saying ”Šta je, jel igra bela mečka?‘ (eng. Is the white bear dancing or what?), the term we use for an event that evokes the curiosity of random passers-by. Apropo this saying, I wonder, who is the white bear and who is the spectator, actually? It might be that the white bear is the observer and he does not need to be tamed.

Not goldening it more than it is, it is the fact that Egypt has been visited for its archeological heritage as a golden civilization that left magnificent traces dating back from the world we have no idea about. This golden coat kicked me after I left Cairo and woke up the following morning on the night train in Luxor. There I understood the massive tourism of the Serbs used to go to Hurgada every year, as well as other people visiting Egypt and seeing just Lux(or). Nobody enjoys truly the 67 layers of dust on their faces while being trapped in the traffic sandwich between the cars, buses, auto-rickshaws, and running pedestrians in Cairo. Rarely who want to live in these conditions. I do not. Yes, we are contributing through tourism and we should keep doing it. No, Egypt is not just a sandy kingdom and Giza. That is all I wanted to comment on.

Again, how to be sure that this is not one more reflection fabricated by a western explorer?

Now, poetry for the poor. (ref. Architecture for Poor, Hasan Fathy)

Granite poverty,

she, however, bravely smiles.

Sculptured, structured valleys

and these little brown eyes.

I dare to feel,

feel quickly and escape.

Never in your skin.

Never in this shape.

My apologizes for just being,

and existing as I am.

I must create a blanket

so I can protect them!

All of them.Scared and aware,

of the white nightmare

my foot in dirth,

completely bare.

My skin somehow shines.

And they stare.Nevertheless, I am the other

I have never seen the crying city before.

My eyes are bigger

then my own hunger.

They are the one,

one of the same.

Non-existing trone,

just a pile of chairs.

The voices are raised,

the voices that dare.

They exist so much,

one can feel it in the air.

A special hug goes to all my children.

“You are being oversensitive.”

I don’t know how often I have heard this sentence before. And to be honest, it took me a while to realize that being oversensitive wasn’t in fact a bad thing. Yes, I was being oversensitive, but what if that didn’t mean I should have let go, don’t care, feel less. It meant that I have a good intuition for what feels right for me and what feels wrong. The problem is that this is often not what people want to hear from you. And I was not intimidated to tell them what they didn’t want to hear. So, I ended up being the complainer. “Oh, Fabienne disagrees with something? Is she again causing a drama? Well, that’s just how she is.” Whether at school, in my dance classes or at home: I would probably get the award of causing dramas.

What is even meant by drama?

It means not accepting everything just as it is. Running the risk of disrupting the apparent peace of a situation. Being uncomfortable. Making people face their wrongs and maybe with-it face certain emotions. Which can be hard to bear. But it also means running the risk of being wrong yourself and creating a drama over nothing. And don’t you dare causing a drama over nothing.

If you complain as a woman, you very quickly fall into a certain drawer. There is an exaggeratedly distorted image of women complaining too fast and too much. When you raise your voice, you are causing a drama. Your actions are constantly on the edge being seen as an overreaction. Keep your voice down, keep your opinion down and most importantly, keep your emotions down. If you do find the courage to speak up, don’t run the risk of mixing it up with your feelings because you will most probably end up being defined as hysterical. Hysterical: women’s favorite word. Defined as hysterical you are not just a concerned person anymore that found itself in a difficult situation it wanted to change or has experienced unfair treatment. No, now you are just “always” overreacting. Hence as a woman, if you complain you have to be even more rational, come even more strong, be even more neutral and base what you experience even more on facts, than man have to do. US-psychologists around Victoria L. Brescoll from the University of Yale noticed that when a woman is angry, she loses her status, no matter what position she is in. Within an experiment they found out that being angry as a man is seen as positive, while coming from a woman it is seen as negative.1 Women should not be uncomfortable. They should care and encourage peace. Because a woman who does not complain and does not get angry, won’t change anything about the inequality between man and women.2 As a consequence there is a tendency of women not expressing their anger and their concerns outwardly. They make it out with themselves. So, while there is this image of women complaining too much, they actually learn from very early age on to be quiet and smile.

Furthermore, as a feminist you might find yourself losing your credibility when it comes to criticizing men as for example a feminist PhD student expresses in the book “Complaint!”: “I think they thought almost that I was looking for it, like a feminist thing, you are always overreacting, blowing things out of proportion because that’s what you see everywhere.”3 It might even come to the point of questioning yourself, your own judgment when you experience sexism. “She tells herself off, even: she gives herself talking to; she tells herself to stop being paranoid, to stop being a feminazi, to stop being a feminist, perhaps.”4 When complaining as a woman and as a feminist you run the risk of being seen as a “man-hater”, one that discards everything men do. Hence everything you criticize is not perceived as being expressed because there is something wrong about what a certain man did but simply because you despise man. You are not listened to and the louder you get, the less you are heard. “The could-be complainer is also the feminist complainer, feminism it-self being charged with complaint through the exercising of old and familiar negative stereotypes (feminists as “man-hater”). Feminist complainers are called vermin, polluting agents who need to be eliminated.”5 Being afraid of endangering their status and their position within a structure might lead to woman not speaking up anymore.

Speaking up and making abuses visible is seen as a danger. It is seen as a danger and tried to be avoided, when it meaningful and impactful. Analyzing who is trying to avoid it makes visible who is in power and who wants the status quo as it is, meaning who benefits from it. “One way a complaint can be dismissed is by magnifying the demand; a demand for “equality and safety” is treated a wanting to bring an end to what or who already exists, or as separatism, a wanting not to share a space or culture.”

Being told that you are overreacting and being oversensitive is very dangerous, as by time you might lose your sense in trusting in your own judgment. We need to learn to trust in our senses. In addition we need to be open for criticism and change. Being sensitive is not something negative and is also not tied to a gender. Everybody should develop a certain level of sensitivity so we can create a space of awareness and of living with and not against each other.

1 See: Hoeder, C-S. (2021): Wut und Böse. München: hanserblau, p.38.

2 See: ebd., p.11.

3 Ahmed, S. (2021): Complaint!, p.105.

4 ebd., p.104.

5 ebd., p.131-132.

Im letzten Teil ihres Buches “Complaint!” erwähnt die Autorin Sara Ahmed eine Reihe von Ideen zu Beschwerden. Einigen von ihnen stimme ich wirklich zu. Und die Sätze sind eine große Inspiration für diejenigen, die sich beschweren wollen.

“I believe in complaining, even when it’s a bad outcome, just creating that record of what happened. I am glad that it exists for me, and that if any questions are raised I have it. I did lodge a grievance, I had a go, I did try.”

“A record can be what matters to the one who assembles it; a record can be a reminder that you made an effort, that you had a go, even if that effort did not lead to institutional change.” (S. 288)

Dieses Zitat erinnert mich an einen Spruch, der mich schon oft inspiriert hat: “Wenn man sich anstrengt, hat man nicht immer Erfolg, aber wenn man sich nicht anstrengt, wird man definitiv keinen Erfolg haben.” Mit Beschwerden verhält es sich genauso: Man muss eine Beschwerde einreichen und sich die Mühe und Zeit nehmen. Letztendlich hat die Beschwerde möglicherweise keinen Erfolg. Aber wir müssen es trotzdem versuchen, um gegen die dunklen Dinge zu kämpfen.

“I leave no trace of wings in the air, but I am glad I have had my flight.”— Rabindranath Tagore

“Even going through an exhausting of processes can have creative potential. Yes, we can be in a state of exhaustion because of that process. But complaints, even formal ones, slow and tedious ones, long and drawn out, can be creative. ”(S. 289)

“I suggested earlier that even when our complaints end up in filing cabinets, we take them with us. I also noted that we don’t always know where complaints go, before they are filed. But even when complaints end up in filing cabinets, they can get out; we can get them out. Filing cabinets are temporary shelters. The more letters written, the more letters to leak.” (S. 298)

Wir alle wissen, dass die meisten unserer Beschwerden im Aktenschrank verbleiben. Der Aktenschrank ist eine sehr verbreitete Methode, um Beschwerden zu vertuschen. Aber er hat einen begrenzten Platz und kann nicht alle Beschwerden abdecken. Wenn wir also weiterhin auf unsere Beschwerden beharren und uns wehren, werden diese Beschwerden irgendwann ernst genommen werden.

Natürlich hat eine Beschwerde viel mehr Aussicht auf Erfolg, wenn sie von einer Gruppe unterstützt wird. Die Realität ist jedoch, dass viele Beschwerden von Einzelpersonen eingereicht werden. Wenn also diese ähnlichen Beschwerden als Kollektiv zusammengefasst und zusammengeführt werden könnten, wäre die Wirkung der Beschwerde sehr groß. “Two heads are better than one.” Die Autorin Sara Ahmed hat viele individuelle Beschwerden zu einem Kollektiv zusammengefasst, um dieses Buch zu schaffen. Das Buch enthält eine große Anzahl von Vorfällen aus dem Leben der Beschwerdeführer und berührt viele Aspekte des Lebens. Ja, es ist die Kraft einer kollektiven Beschwerde.

Remember how during our first session in class we talked about productive complaining?

Well, please let me do the complete opposite today and just complain,

because I really feel like complaining.

First of all, its winter.

People hate winter.

It is dark, it is cold, the days are so short,

but it’s also a nice topic to complain about every day.

Normally when I feel the need to complain I talk to my mother.

She is the “complaint-receiver” of the family.

After a hard day of working, she comes home, where she finds 10 missed calls from her 4 children and a husband, everybody ready to lay off the burden they collected all day long.

But I could not reach her.

Please let me complain here about what we don’t want to talk about anymore:

I want to complain about the ongoing pandemic. I want to complain about my mental state that has pulled me into a down again. I want to complain about humanity still not able to deal with social injustices and climate change. I want to complain about the weather.

But, who to address this to?

Some things are (seem?) too big to complain about productively.

All you are left with is just complaining.

This makes me think about whether we have never learned how to complain productively within the right structure. Watching a lecture from Sara Ahmed I found it interesting when she talked about certain procedures that are applied when you voice your concern to the official complaint procedures of institutions. They receive you, they listen to you, they nod, and they say yes. They say yes, they will accept your complaint and deal with it. It gives you a feeling of satisfaction. You were able to let off steam, you feel like you have advanced in your process of dealing with your issue. But then nothing happens. You went through the whole procedure, but in the end, you sent the file and by filing it you might put it to rest forever. The problem is that going through the whole procedure gives you a feeling of being active and of accomplishment without something happening for real. Because what happens from the part of the complaint-receiver is simple “nonperformaty”. There is a gap between what is supposed to happen (according to policies and procedures) and what is really happening1. You have to push institutions to follow their own policies and even then, it can take a lot of time as they hope that by time you will just let go. Hence in the end, all you did was letting off steam: an explosion is avoided by the one that receives the complaint2. By filing your complaint, you got a feeling of being productive even though in fact you were not.

When I think about it, I suspect the same thing happens when you complain to friends instead of directing the problem to the subject involved. I do think that it is very important to talk to your friends about weighs you down: you will realize you are not alone and learn to sort out your thoughts before you impulsively address them. But the problem might be that you complain so much to your friends and just anyone that you might not feel the urge to complain to the right person anymore. The complaint is never received, the steam is off, but nothing has changed: unproductive complaining.

Part of the issue might be that often you just don’t know who to address your complaint to. I have to be honest and say that before reading this book, I was not even aware that there are places where you could hand your issues to. And this is for sure again part of the problem why complaints are not officially dealt with. There is no general awareness of what to do when you find yourself in a state that is unbearable, where you or someone else is wronged, where you are looking for change. Looking at complaining and seeking change in within institutions there is strangeness in the aspect that there are in fact procedures set up for complaints, but it seems like everything is done for you to not use them and if you come to the point of using them, they seem to prevent themselves. Complaint-procedures are not accessible. “A complaint procedure is how you learn what to do, where to go, in order to make a complaint.”3 Before you can get through with a complaint you have to work your way through the fog of knowing how to do it. This is why you might not do it at all. And the less these procedures are used, the harder they are to find.

We need to learn how to make complaining accessible. We need to learn how to complain productively. Because for now complaints seems to be done to prevent us from complaining.

Is our system not made to receive complaints because it is not made for change?

1 See: Ahmed, S. (2021): Complaint!, p.28.

2 See: Sara Ahmed, Complaint as Diversity Work, Joan S. Korenman Lecture, March 2019, ab min 8:15.

3 Ahmed, S, (2021): Complaint!, p.31.

Nachdem ich den Teil drei “IF THESE DOORS COULD TALK? ” gelesen habe, bin ich von dem Artikel überrascht, in dem erwähnt wird, dass ein Hochschullehrer eine Studentin sexuell missbraucht hat. Da ich diesem Bereich zuvor weniger Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt hatte, fand ich diese Situation sehr befremdlich. Also habe ich im Internet nach der Lage an chinesischen Universitäten recherchiert. Nachdem ich die wirkliche Situation herausgefunden hatte, wurde mir klar, wie ernst diese Angelegenheit ist. Erst vor kurzem gab es ein Beispiel, bei dem eine Studentin ihren Lehrer wegen sexueller Nötigung anzeigte.

Allein die Zahl der Enthüllungen ist erschütternd, es ist schwer vorstellbar, wie viele weitere Vorfälle nicht ans Licht gekommen sind. Viele Studenten haben nicht den Mut, sich über ihre Lehrer zu beschweren. Einerseits glauben Studenten, dass der Lehrer ihre Note und damit indirekt auch ihre Zukunft in den Händen hält. Andererseits werden wir in China dazu erzogen, unsere Lehrer zu respektieren und auf ihre Lehrer zu hören. Das Bild des Lehrers ist für die Schüler immer ehrenhaft, rechtschaffend und heilig. Aber eines Tages schließt der Lehrer plötzlich die Tür, zeigt ein anderes Gesicht und will den Studenten ohne Scham sexuell angreifen. Ich bin sicher, dass die meisten Studentinnen an diesem Punkt überfordert sind. Selbst wenn sie sich wehren und es schaffen, die Tür zu durchbrechen. Aber auch danach bleibt ein tiefer Schatten auf ihnen zurück. Das kann zu Depressionen oder schlimmstenfalls zum Selbstmord führen. Das sind nicht meine Mutmaßungen, sondern Fälle, die tatsächlich passiert sind.

Wie einige der im Buch “Complaint!” angeführten Beispiele zeigen, findet diese Art von sexuellem Übergriff im Wesentlichen zwischen Masterstudenten und Professoren oder Doktoranden und Professoren statt. Warum? Ich denke, der Grund dafür ist, dass die Interaktion zwischen Master und Professoren eher eins zu eins stattfindet. Anders als bei Bachelorstudenten, die in einer Klasse, einer Gruppe oder einem Kollektiv auftreten. Sie sind viel stärker, wenn es um ungerechte Behandlung geht. Masterstudenten sind üblicherweise eine einzige Person, deshalb sind sie sehr schwach gegenüber dem Professor. Je anfälliger eine Studentin für sexuelle Übergriffe ist, desto größer ist die Wahrscheinlichkeit, dass einige Professoren es tun wollen. Aus diesem Grund sind Masterstudenten und Doktoranden die Gruppen, die am häufigsten von sexuellen Übergriffen betroffen sind.

Es ist nur meine persönliche Interpretation. Aber diese Ereignisse erinnern mich auch an einige der Themen, die von Masterstudenten in China häufig diskutiert werden. Einige Master sagen, dass sie in ihrem Masterstudium eher Assistenten ihrer Professoren sind und dass sie neben ihrem Studium viele zusätzliche Arbeiten leisten müssen. Ein Großteil dieser Arbeiten sind unbezahlt und helfen ihnen in keiner Weise weiter. Je mehr Arbeit sie leisten, desto wahrscheinlicher ist es, dass sie ihre Masterprüfungen bestehen. Einige andere Masterstudenten erwähnen auch, dass sie für Feste oder den Geburtstag des Professors jedes Jahr teure Geschenke machen müssen. Denn diese Geschenke können den Professor glücklich machen, und wenn der Professor glücklich ist, wird er oder sie in der Lage sein, einen erfolgreichen Abschluss zu machen. Aus diesem Grund sagen viele Masterstudenten, dass sie nach ihrem Abschluss keinen Kontakt mehr zu ihren Professoren haben. Alle Kontaktangaben werden unverzüglich gelöscht. Tatsächlich trauen viele Masterstudenten sich nicht, sich an ihrer Universität zu beschweren. Ob die Macht des Professors an der Uni zu groß ist?

Natürlich behandeln nicht alle Professoren die Masterstudenten so. Es gibt auch viele Professoren, die sich korrekt und hilfsbereit gegenüber den Masterstudenten verhalten. Nach dem Abschluss halten sie den Kontakt und pflegen ein gutes Verhältnis. Dies ist eigentlich ein Wahrscheinlichkeitsereignis: Wenn ein Masterstudent seinen Professor ausgewählt hat, entscheidet sich auch der Verlauf des Studiums. Dieses Bildungssystem kann einige Nachteile haben und ist von vornherein ungerecht. Die Zukunft der Masterstudenten liegt nicht in ihrer eigenen Hand, sondern hängt davon ab, ob sie das Glück haben, einen guten Professor zu finden. Und wenn die Entscheidung einmal getroffen ist, kann sie nicht mehr geändert werden.

Ein Zitat aus dem Buch “Complaint!” lautet:

“I think of narrow corridors. They can be what you have to go through to get somewhere, to reach an open door. A professor can become a nar- row corridor: who you have to go through to get somewhere, who you have to go through to reach an open door. A going is often narrated as a gift. Those who abuse the power given to them by virtue of position often represent themselves as being able to open the door for others. When an open door becomes a gift, an open door can also be a threat.” (S. 230)

One student said of her complaint, “It just gets shoved in the box.” Another student said, “I feel like my complaint has gone into the complaint graveyard”… Doing things in the proper way, doing what you are supposed to do, can lead, does lead, to a burial. If a burial should not happen but does happen, then burials might not appear to have happened; a burial can disappear along with what has been buried. 1

Growing up as a bookworm, I sense a subtle tinge of shame admitting that I have only read a handful of books during the past few years. In my defence, the past few years were anything but normal. They seem like a never-ending train of tragedies, always keeping you on edge, wondering if you should perish the moment because what is yet to come is going to be even worse. Years of therapy were undone in a matter of months, and my already dwindling attention span got absolutely annihilated.

Choosing to take part in a course where the main task is read the damn book does not seem like the wisest decision. But I wanted to push myself, and having been familiar with Ahmed’s work, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to immerse myself in the new book, finding different, personal, and artistic ways to approach it.

And I’m gonna be honest – I have become a slow reader. But to my surprise, Complaint has been a rather easy read. Now, it might be condescending to describe a book by a scholar who’s been a professor, an academic worker, and a diversity worker as an easy read. Nothing this woman has done in her life could be spoken of in the same breath as anything easy . And a book that deals with such sensitive, important topics such as discrimination and harassment, and all the ways you could fail if you seek justice – How could it be easy to read?

Yet part of what makes Ahmed such an important feminist scholar is her ability to write in a way which is both accessible and cautiously intimate. Her aim is not to write specifically for people with a similar background or knowledge, at least not in this specific book, and not in, say, Living a Feminist Life. What we have here is not a textbook, you don’t have to put a bunch of reference books next to you to get what is discussed, all you need is being willing to become a feminist ear, as Ahmed herself.

Complaint?! Is thereby an accessible book in both the way that it is written and the way it is structured. Before reading the book I listened to a few of Ahmed’s talks about her research throughout the writing process and the experience of reading the result is very much like listening to her. Complaint?! is an unapologetically emotional book. Is a collection of testimonies, as Ahmed likes to call them, yet not a simple report. If there’s one thing I have learned from this book is that there are already enough reports on complaints in this world – somewhere in a cabinet probably. She plays with words carefully, not too much to be a distraction but just enough to make sure that she still has your attention, which makes the text – if I dare judge – poetic and very human.

If a complaint is made to create more time and more room, a complaint can take time and leave you with even less room. The less time you have, the less room you have, the more conscious you become of who is given time, who is given room. 2

Using metaphors – sinister ones: doors, burials, bodies that have stopped functioning… -and repetitions, Ahmed makes sure that a common language, a common understanding is being shaped gradually between her and the readers – who may or may not have been in the situations described in the book, or may or may not have privileges that would make them unlikely to ever experience them. And may or may not have the attention span of a squirrel after having spent what seems like a lifetime in isolation and a constant state of fear. And it’s amazing how empowering this sense of having achieved a common language is. How relieved you could feel when you hear what you could have not expressed in someone else’s words. Even if the relief is followed by a vague sense of helplessness, it is still something. It’s like putting feelings in words makes them justified, gives them a face, their very own identity. And it might make them scarier at the beginning – “words can never hurt me” says a liar or a fool – but that’s a start.

I think.

How do you pull yourself together to share an experience if an experience is of breaking apart? 3

I would like to start this post by stating: Everyone is allowed to complain, anytime, anywhere, concerning any issue.

What does this sentence provoke in you? Do you agree? Do you disagree?

I myself have to say that I am not so sure about this, even though I am also not so sure who should be deciding over this. Complaining means expressing discontent or dissatisfaction about something, making an accusation, stating that something is (done) wrong. I want to specify here that I will focus on complaining when you are treated unfairly, such as for example by a person, a procedure, or an institution.

Who is allowed to complain? A complaint starts with the reason why you want to complain, and this reason starts with a feeling. A feeling of something being wrong: feeling hurt, suffocated, excluded, offended, hence unfairly treated. And this is where it already gets complicated. “Am I allowed to complain?” starts with a: “Am I allowed to feel wronged?”. The fact that it is so difficult to define right or wrong, especially when emotions are involved, makes the whole process somewhat subjective and easily determined in the end by whoever is in power (with this often being whoever you complain about). So, who decides over right or wrong? The complainer or the “being-complaint-to”?

Who is allowed to complain? The right to complain is also a matter of privilege. On this issue there is a conflict between the fact that some people are too privileged to complain and some not privileged enough to get through with a complaint. Are you the right person to complain? While going through with a complaint “we learn how only some ideas are heard if they are deemed to come from the right people; right can be white.”1 There is absurdity in the fact that if you are in the position to make a complaint, hence if you are suffering under certain power relations that put you in an unjust situation, you are most probably not being heard. “You might not feel confident that your complaint is being taken seriously when your complaint is about not being taken seriously.”2 Thus when you chose to complain you take a huge risk, which might lead to self-damage. More than often, you are already in a precarious situation and can’t afford to lose your job or hurt your image. If you find yourself in this situation, you might be reminded of your dependence on the one you want to complain to. Hence your issue is not being taken seriously by those in power to do something about it. In addition to this “complaints are more likely to be received well when they are made by those in power.”3 Those who are already more influential are more likely to get through with their complaint. This is widening the already existing inequality gab in hierarchies.

Who is allowed to complain? Those who are heard are those who are in the “right” place to complain: those in a stable state, those with enough power, those who have the right connections, those with the resources to do so. But isn’t it ironic that when you find yourself in a situation of suffering, without support, and hence file a complaint, you are not supported by the system? And if you are in the “right” place to complain you are actually not really in the right place to complain, meaning the reason why you complain might not be that severe, because you don’t find yourself in a precarious situation.

In conclusion when is complaining justified? When is your state alarming and legitime enough to be entitled to do so? When are you well enough positioned to complain? When are you allowed to take away people’s oh-so-precious time to criticize and tackle the system they are so desperately trying to uphold? To complain is to make yourself vulnerable. Be aware of the burden that comes your way, whether it is the burden of your privilege to be able to do so, or your struggle or even your inability to get through with it.

1 Ahmed, S. (2021): Complaint! 2021, p.6.

2 ebd., p.21.

3 ebd., p.24.

Welcome to the Strange Fruits episode of the Voiced Displeasure. Maybe the least favorite one, but tasty, for sure. Poetic, inevitably. The main protagonist relates to the 3 sections: Juice, danger, and joy; Systems, sugar, skin, and stain; The land of rightness, emptiness, and gray color. Next time instead of the external keyboard, you might bring the fork. Have you ever heard a fruit talking? Did you find it uncomfortable? Understandable. No judgments. This is a safe space. Let´s bite.

”I am a little parasite stuck on your ceiling, watching and waiting for the right moment to grab your face. I am an angry skeleton under the thousand layers of this skin blanket. I want to get out of my colonized past.

I am the one you want to squeeze. My lemonish, bitter body is hanging on the walls of your borders. Experience the haptic touch of this nectarous object – me. Me, the stranger. You – domestic. Me – the dirt on Your floor. You – the boundary. My amorph shape stands out from the crowd, breaks the concrete, entering the void. I produce joy. Try me. I am a violent inhabitant trying to break your comfort. I am the stain spot of this system.

These little hands were holding the poles in the foreign trains and buses, being observed. My hands are being watched – the way they move, how the fingers fold and dance around the strange objects. I am the sensation. My legs are making the gaps between the foreign feet, stepping into the unknown. Kissing the strange ground, while dropping the strange juice into the dry field. My earlobes are made of sugar, melting in the strange air. My lungs are suffocating from the bizarreness of this place. Its mystifying inner shakes my foreign outer. Its breeze freezes me. I must get out.”

THE FRUITS FROM A STRANGER

MANIFESTING THE JOY OF THE DANGER

My charming existence.

My strange fruits.

Its juicy resistance,

that shoots the roots.

The alluring, strange chain,

keeps my existance remain.

My omnipresent stain

melts the acid rain.

Welcome to Saxony, the land that tears the skin of the beast. Welcome to the act of peeling one’s outer. Chemnitz means stones, coming from the language that I can understand, for some reason. Welcome to Chemnitz, friends. Welcome these words that are coming and be free to dive into the experience.

”The strangeness climbs through my spine, from the bottom. Slowly and precisely it covers the whole backside. I feel the structure and heaviness of my skull. My earlobes are collapsing. My head leans towards the shoulders as if it is going to fall. I feel alienated from the outside.

Some parts of my body feel numb. There is a space around my inner skin that I have no contact with. I turn my head to the right I look at one point. My attention stays in the corner of my eye creating the tension of the eye muscle. I can see the small humans inside a human, I sense how they move around me. I see the shadows of these bodies, I feel the coldness piercing my outer strongly through the borders. I AM THE OTHER. The other on many that are the same.

I slowly pull my own inside towards the outside shell. I humbly tore the skin of a creature. I peel the layers of its skin and try to get out. It lasts and feels like forever. I am the stain spot on this map. Pulling. Vibrating. Pushing. I am so alive.”

PS: NEVER EAT THE FRUITS YOU HAVE NEVER SEEN BEFORE.

* “Strange Fruit“, Abel Meeropol, Billie Holiday, 939, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strange_Fruit

The displeasure of Strange Fruits was inspired also by the book „Strange Fruit“ by Lilian Smith, 946, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strange_Fruit_(novel).