A close friend called me one afternoon a few weeks ago and asked me how and what I was doing. “I am doing great. I am currently taking pictures of benches in the train station”, I answered. This happened right after I read Chapter 4 of Sara Ahmed’s »Complaint!« in which she addresses the issue of power structures, more specifically occupied spaces. With the following quote, she primarily referred to mental spaces and invisible institutional structures that exclude and discriminate against people with certain characteristics:

“When spaces are intended for specific purposes, they have bodies in mind.”

(Ahmed 2021: 137)

However, it reminded me of classical music being played loudly in train stations during the night, spikes on balustrades and benches divided by arm rests. Those are all types and mechanisms of »Hostile architecture«. Hostile architecture describes design practices that shape public spaces to allow only the use intended by the owner (cf. Hu 2019). Through this, “a subtle expression of social division through urban design, mostly associated with the homeless” is transported (Karthik & Sanjiv 2020: 247). More specifically, hostile architecture purposefully discriminates, especially against minorities.

»Hidden Hostility« by Theresa Güldenberg & Magdalena Meißner

The art project »Hidden Hostility« by Theresa Güldenberg & Magdalena Meißner aims to create awareness for invisible design strategies by directing the view of people on the pedestrian zone on examples of hostile architecture. To achieve this, the artists selected archetypal examples of hostile architecture expressed in benches and seats and dealt with them in various installative ways. (cf. Güldenberg & Meißner 2022)

For instance, they have wrapped various materials, like barrier tape, foam material and metal wire around public seating facilities. Watching the wrapped benches, it becomes visible how either gaps or arm rests ensure that nobody can lie down or even linger comfortably for a longer time.

In addition to using different materials, the artists also employ statements, graphics and questions to draw attention to the mechanisms of discrimination and control inherent in the public furniture presented. Metal signs, which are attached to benches and seats by Theresa Güldenberg & Magdalena Meißner, play a particularly central role in conveying these statements. Phrases like “Der Feind ist der Freund dieser Bank” (Engl: The enemy is the friend of this bench) (Güldenberg & Meißner 2022) and illustrations, like the ones on the pictures below, express criticism and stimulate the pedestrians to think.

In the various installations of “Hidden Hostility,” the two artists repeatedly refer to a central point that constitutes the core of their work. Thus, they state that hostile architecture serves social control, unnoticed but aggressively expressing political power in public space. (cf. Güldenberg & Meißner 2022)

»Hidden Hostility« and »Complaint!«

In addressing design mechanisms that are politically used to discriminate against minorities, the artists take up what Sara Ahmed refers to as invisible power structures. The key point here is that these mechanisms usually remain hidden. In the case of hostilely designed seating in public spaces, this means: as long as you don’t have to spend a longer time in public, or even sleep there, you won’t be irritated by uncomfortable benches. Invisible power structures define whose feelings matter more (cf. Ahmed 2021: 169) – the feelings of supposedly “normal citizens” are more important than those of homeless people.

On closer examination of hostile architecture against the background of this argument, it becomes clear: public space becomes an occupied space in Ahmed’s sense through hostile design mechanisms. As Sara Ahmed puts it: “you notice a structure when it stops you from getting somewhere or from being somewhere: it can hit you” (Ahmed 2021: 141). This means that even if our society is claimed to be social and solidar, it systematically discriminates against homeless people.

The way Theresa Güldenberg and Magdalena Meißner approach this fact in their installations can be understood in itself as an act and expression of a complaint. In particular, the metal plaques with messages are an expression of complaint in Ahmed’s sense and, at the same time, have an activist character due to the aim of making people think. However, the artists do not complain about a specific institution and thus not to a specific person in charge, but address society as a whole. With their work, they try to invite people to hear their thoughts, pick them up and turn them into other complaints.

Reflection on hostile architecture

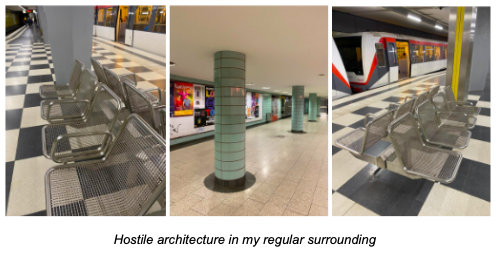

Understanding both, the art project »Hidden Hostility« and Sara Ahmed’s book »Complaint!« as an invitation for reflection, I took pictures of hostile architecture in my regular surroundings, as mentioned in the beginning.

In these pictures you see a train station that I frequently use – a train station that is equipped with divided benches and that plays loud music in the hallways the whole night. A train station that claims to be part of public transport, but in fact excludes people who can not afford to take trains, but intend to use it as a shelter in the public. Feel free to do the same and scan your environment with a critical eye, being conscious that hostile architecture turns our environment into an occupied space. And feel free to complain about it in a creative way.

References:

Ahmed, Sara. Complaint!, New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2021.

Güldenberg, Theresa; Meißner, Magdalena. Hidden hostility, 2022.

Retrieved from: https://www.burg-halle.de/zwischendenstuehlen/magda-theresa/.

Hu, Winnie. ‘Hostile Architecture’: How Public Spaces Keep the Public Out, 2020.

Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/08/nyregion/hostile-architecture-nyc.html.

Karthik, Chadalavada; Sanjiv, E. Sripadma. Defensive architecture – A design against humanity. In: International journal of advance research, ideas and innovations in technology, 2019, Volume 6, Issue 1).