Last month, three graduate students in Harvard University’s Anthropology department- Margaret G. Czerwienski, Lilia M. Kilburn, and Amulya Mandava – filed a 65-page lawsuit against the university over the way it has handled sexual misconduct complaints involving anthropologist John Comaroff. According to the lawsuit, Camaroff “kissed and groped stu-dents without their consent, made unwelcome sexual advances, and threatened to sabotage students’ careers if they complained. When students reported him to Harvard and sought to warn their peers about him, Harvard watched as he retaliated by foreclosing career paths and ensuring that those students would have ‘trouble getting jobs.’”1

At the centerpiece of the lawsuit are the comments Comaroff made as Ms. Kilburn met him in his office to discuss her planned fieldwork in Africa. Ms. Kilbun recalls how Comaroff graphcally described she “’ would be raped’ or killed in certain parts of Africa” if she chose to do her work field there since she is in a lesbian relationship. Comaroff also reminded Ms. Kilburn of “the power he now wielded over her career,” 2 and as she tried to change adviser to avoid Comaroff, he cut her off from other professors.3

The lawsuit, New York Times writes, is “the latest strike in more than a year of allegations being parried back and forth in the case against Dr. Comaroff”, many of which are documented in The Harvard Crimson, the student newspaper, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. Among them are anonymous allegations dating back to before Comaroff started working at Harvard in 2012.4 According to the lawsuit, during the process of hiring Comaroff, the Chair of Harvard’s Department of African and African American studies was warned by Comaroff’s former students at the University of Chicago, where he was considered a “predator” and a “groomer“. They “could have influenced the hiring decision, supervised Comaroff, or implemented safeguards – and protected Harvard’s students.” Yet they welcomed and “empowered Professor Comaroff,”5 the lawsuit says.

New York Times reports that Comaroff was placed on unpaid leave after the school’s investigations found that he violated sexual harassment and professional conduct policies, “but he was not found responsible for unwanted sexual contact.”6

The lawsuit surfaced many unsettling issues, among them the allegation that Harvard accessed Ms. Kilburn’s private therapy records without her consent and revealed them to Comaroff, who then used them to discredit Ms. Kilburn’s accusation. 7 I will link the lawsuit and a few well-rounded articles about the allegations and how they were handled at the end of this post. Following the case feels like reading an almost real-time case study in Complaint!, and especially has reminded me of the section COMPLAINTS AND COLLEGIALI-TY in the book:

The department was warned about Comaroff’s previous misconduct at the University of Chicago and him being “surrounded by “pervasive allegations of sexual misconduct”. Harvard hired him anyway. 8 “Sometimes you hire people whom you like, or who are like those who are already there. “ 9 Ahmed writes. She notes that a broad instructional problem of harassing and bullying often indicate “an informal or casual culture around hiring”, recalling a lecturer who had told her that people often talk about candidates as “he’s the guy you’d want to have a pint with.”10

“When you make a complaint, you often learn about how power is wielded.”11 before the lawsuit, 38 Harvard faculty members signed an open letter supposedly questioning the process that sanctioned Comaroff. The letter is, however, also a love letter to their “excellent colleague.”

We the undersigned know John Comaroff to be an excellent colleague, advisor and commit-ted university citizen who has for five decades trained and advised hundreds of Ph.D. students of diverse backgrounds, who have subsequently become leaders in universities across the world.12

They also addressed the rape comments, adding that they would be “ethically compelled to offer the same advice” if they were to advise Ms. Kilburn regarding studies in Africa.13 Harvard Law Professor Janet Halley issued a statement calling the comments “legitimate office-hours advice.” Professor Jean Comaroff – yes, Comaroff’s wife – criticized the complaints in her statement as an “attack on academic freedom.”14

“When some colleagues are friends, they are who end up being defended.”15 Ahmed writes. The faculty members jumped to defend their excellent colleague without being informed about the details of the complaints. That’s not my assumption – but their words. Shortly after the lawsuit went public, all but three professors said they wish to retract their names from the letter.16

What has happened? I am making assumptions here – but what if their change of heart and retraction from supporting their predator college was less because they suddenly noticed their lack of information and the impact of their word on the students17, and more about their reputation being on the line? The lawsuit did receive attention, much more than the scattered complaints filed in the previous year. All of a sudden, the discussion was not taking place behind closed doors and between colleagues. People were talking about it on the internet, it was receiving media attention. Harvard is a big name, and the cat is out of the bag. (and has slid through the closing door, smart cat)

According to the lawsuit, Comaroff once compared himself to Harvey Weinstein at a dinner with faculty and graduate students, saying “They’re coming for me next!”18 This is telling of how untouchable he felt. But also, ironically true as in the way his colleagues were quick enough to distance themselves from him when it got clear that the issue is getting out of hand. Such was the case with the disgraced Hollywood mogul.19

His wife, Jean Comaroff, who was also present at the dinner event, later belittled the sexual harassment complaints commenting “Whatever happened to rolling with the punches?” 20

Just roll with the punches. Just loosen up. Feminists: so sex-negative. So uptight. Don’t over-react, don’t be so divisive. 21

Back to the rape comments. The way Comaroff pals and colleague tried to downplay them reminded me of a section in Complaint!, where physical violence towards a student who was trying to “flee” from the office of the head of the department was apparently “on par with a handshake.”22 Comaroff thinking loudly about how his student is going to get raped is described as “legitimate officehour advice”23 As Ahmed writes, “violence can be removed from an action by how an action is described.”24

The lawsuit further criticizes Harvard’s Title IX office, pointing out that the office did not act on complaints regarding Comaroff and has time and again discouraged students going down the formal complaint route: Ms. Czerwienski was told in October 2017 that filing a formal report would be “futile”25 Ms. Kilburn states that her complaints on May 2019 were “was met with predictable indifference”26 , even though the officer knew who Ms. Kilburn wanted to talk about. At a recent demonstration in the Yard Kilburn said “The Title IX system was supposed to be the solution, Instead, it’s become part of the problem.”27

I was listening to the sound of machinery: the clunk, clunk that was telling me that inefficiency is not just the failure of things to work properly but is also how things are working.28

Harvard enabled and protected the predator for years, and that in a field as small as anthropology, where a downvote from a professor as influential as Comaroff could be the end of the academic career.29 only to take action when the students decided to go public.30

As of February 21, several of Harvard’s tenured Anthropology faculty asked. Comaroff to resign, stating that they have “lost confidence” in him as a professor.31

Is this a good ending? I genuinely do not know. One (possibly) destroyed academic career after years and years of predatory and abusive behavior, harassment, ruining careers and lives. What if it was a smaller university? Would the story still have been covered by New York Times or the Guardian? Would “going public” have made a difference?

I end this short report with Czerwienski’s final words at the recent campus demonstration:

We need to keep insisting as loudly as we can, as often as we can, in as many places and to as many people in power as we can, that this system must change.… The University wants us to throw our little rally and go away. But it’s our job to make sure they’ve got another thing coming.32

The Harvard Magazine writes: “A few minutes later, the demonstrators dispersed, amid chants of, ‘We’ll be back, we’ll be back!’”33

Amen.

Recommended Readings:

The complete lawsuit

https://www.thecrimson.com/PDF/2022/2/9/Czerwienski-et-al-v-harvard-filing/

New York Times: A Lawsuit Accuses Harvard of Ignoring Sexual Harassment by a Professor

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/08/us/harvard-sexual-harassment-lawsuit.html

New York Times: After Sexual Harassment Lawsuit, Critics Attack Harvard’s Release of Therapy Records

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/15/us/harvard-kilburn-therapy-records.html

The Cut: All the Alarming Allegations in Harvard’s Sexual-Harassment Suit

https://www.thecut.com/2022/02/harvard-sued-for-institutional-indifference-to-harassment.html

For many, to complain is to become more visible and thus more vulnerable. To be under scrutiny can feel like those around you, who surround you, are waiting for you to trip up. And maybe it feels like that because it is that…..To stand out, to be seen, is to live under “the sign of trouble.” Given that complaining can make you stand out even more, complaining can heighten your sense of being targeted at the very moment you try to stop yourself from being targeted.

note: to simplify the formatting I have just simply put all the sources at the end of the text. For the detailed citation check out the file on Moodle or leave a comment.

“With my will, I have to be optimistic. If not, I would just kill myself.” says the Chilean-born and New York based architect, photographer, and filmmaker Alfredo Jaar during an interview with the Guardian, smiling playfully. It made me laugh out loud, not with joy, but relief. I joke about killing myself all the time – well, not all the time. But enough to make my friends uncomfortable – and I always have to explain that I won’t do it, I’m not planning to end my life. Not only because – Jaar quotes the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran in that interview – “It is not worth the bother of killing yourself, since you always kill yourself too late.” but also because I, too, have this will of going on. A blessing and a curse.

Jaar thinks of himself as “an architect who makes art”, and rightly so, given that he graduated from his architecture with a poem. He aims to raise awareness and to create empathy, to make us look at what we do not want to see, don’t have the heart for it, maybe – but not at the cost of trivializing suffering or humiliating the victims, without relying on cheap thrills and easy provocations.

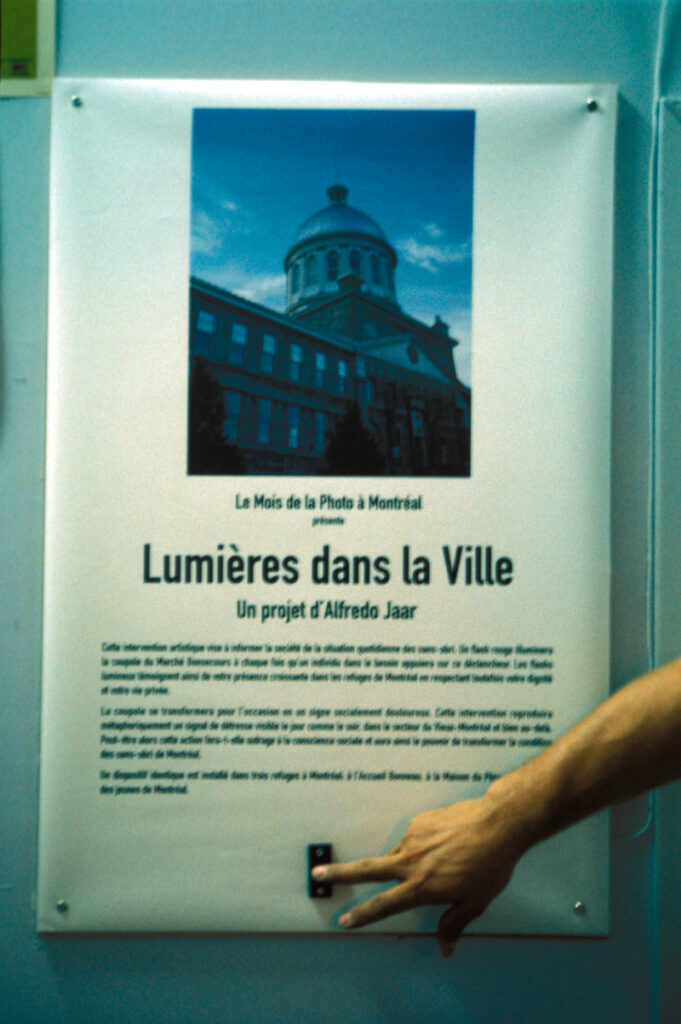

An example of this would be the project Lights in the City (1999) – a project designed to draw attention to the burgeoning issue of homelessness in Montreal.

The artist installed red light on the Copula of the Marche Bonsecours, a landmark monument in the center of Montreal. The lights were connected to homeless shelters located 500 yards from the building. When a homeless person entered one of the shelters, they could press the button that would make the top of the building glow red.

The historic landmark had burnt around five times before this project came to fruition. The glowing red light could therefore be interpreted as yet another fire, Jaar says. But the main message was far more important. Jaar wanted the building to become a “permanent monument of shame” We come to ignore photos and video reportages, at some point, eventually. As we are surrounded by too many of them. Too much suffering you’d become numb, and distracted by the next photo advertising the dream vacation.. He does not want to be a part of that.

You see an image of poverty here, you see another tragedy there. You see a couple of headlines and then see you see advertisements for a vacation for Hawaii. And so these images of pain, of suffering, are drowning in a sea of consumption.

For this reason, and also because he did not want to expose the homeless people through photography, the route was taken to make a historical building in one of the richest cities of the world the very symbol of the issue of homelessness. One might become indifferent to the images of pain, of suffering, it is, however, much harder to ignore that each time the building lights up with that bright, intimidating red, a homeless person has pressed the button. It was Jaar’s way to move the city by the sheer number of the people who did not have a place to call home – without humiliating and dehumanizing them.

The project was canceled six weeks later by the mayor. “With these projects you change so little” says Jaar. Speaking one of my dark thoughts every time I find myself admiring an installation, a performance, an artistic idea aiming to bring about positive change – They change so little.

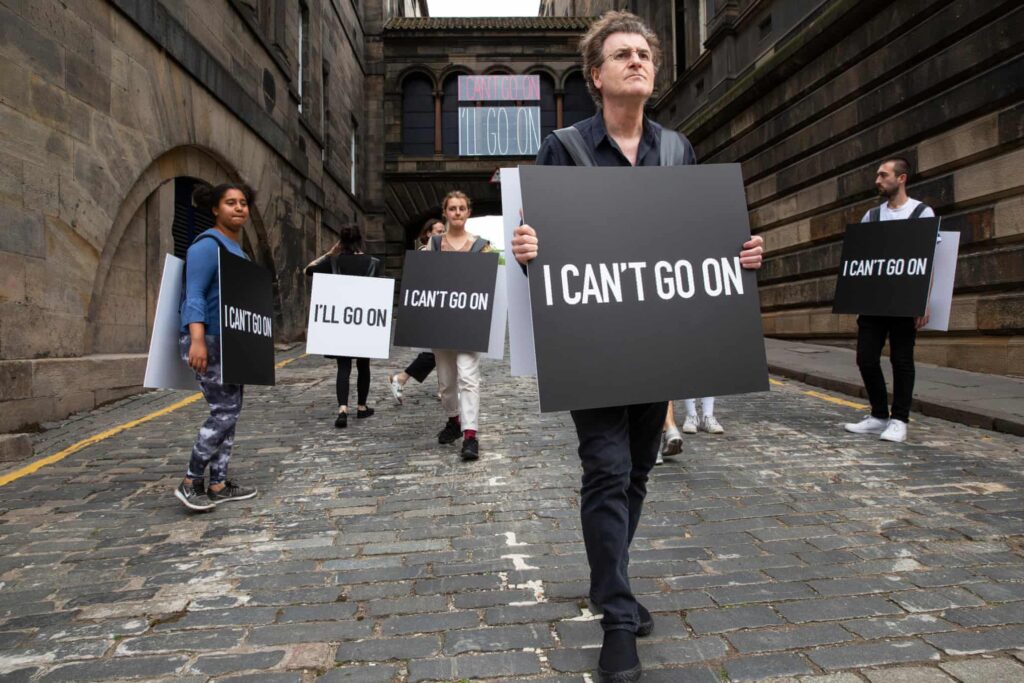

Yet Jaar, as mentioned in the beginning, has to be optimistic. A message conveyed with his public artwork at Edinburgh art festival 2019, I Can’t Go On, I Go On. Taken from the ending words of Samuel Beckett’s The Unnameable. During the festival performers would wear sandwich boards with I Can’t Go On on their chests, I’ll Go On on their backs.

“It’s about our incapacity to change this reality, even though I keep going, I keep trying. Because this is the only thing I know,” Jaar says. His optimism also manifests itself in his decision to dedicate a third of his time to teaching. He believes in the younger generation. “Perhaps someone who sees his Edinburgh piece this week will be inspired to make their own work. Perhaps they will offer us a new vision that can help us navigate the darkness.”

A Complaint, Ahmed writes, “raises the blind.”, which parallels with how Jaar uses his art to draw the attention of the public to the matters left undiscussed or ignored. The homeless shelter next to the Capula in Montreal was “invisible, just like the homeless were invisible… They were overlooked, as a garbage can or a lamppost is ignored” The Lights in the City project gave them back the humanity, made people recognize their existence, even through a smile. The issue was also raised in the press. “We gave them a brief, hopeful moment when they regained their humanity,” says Jaar, adding to the statement that he and his team wanted the Capula to become a permanent monument of shame. “Other shelters wanted to join us and get connected” implying that originally, there was a long term plan. Each night, the historic building was to burn red, burning again and again and again, reminding the city how it has failed to protect its most vulnerable. The homeless were the living, breathing proof of this failure and their invisibility the result of the most simple coping mechanism known to man: Avoidance.

Violence is often dealt with by not being faced. It is then as if the complaint brings the violence into existence, forcing it to be faced. Perhaps this is why complaints are often heard as forceful. For those who received the complaint, who heard the sounds she made, it was the complaint that alerted them to violence. A complaint is how violence is revealed; a complaint raises the blind.

The mayor, I assume, dealt with the problem by dealing with what was raising the problem. “When you expose a problem you pose a problem.” The homeless went back to their state of invisibility, ignored as a garbage can or a lamppost, and people went back to ignoring them, living their day-to-day life, the burden of guilt upon seeing the Capula burning bright off their shoulders. I do not blame the people, of course. Dealing with the issue of homelessness is a problem beyond individual responsibility. Yet with the attention of the public and the press being withdrawn, there was so little left to impose a degree of moral pressure on the authorities. “I fail all the time.” Jaar told the Guardian. “You change so little.”

Having jaar’s intention in mind, one might argue that the project “failed” in ways more than one: he recalls running into some drunken men one night, wandering in the streets and cheering with joy as the red lights in the capula brightened. It’s hard to imagine someone reading Complaint! or listening to one of Ahmend’s speeches and missing her point, yet conveying a message through art always runs the risk of misinterpretation. Jaar’s Lights in the City was no expectation. “You cannot predict what will happen when your work is in the public space.” says Jaar.

Demonstrating a horrible truth through art might leave you with something that is, in the eye of the beholder, solely something beautiful to look at. However, I’d dare say that more people would be willing to visit a “cool performance art”, than reading a text book on sexual assault. But only one of them in guaranteed to convey the message the creator is intending to.

“Many of the stories I have collected in this book seem to be stories of working very hard not to get very far.” Ahmed admits this vague hopelessness near the end of the book Complaint! This cold fear that would turn your stomach. We’re changing so little. But she proceeds to add: “a complaint is a way of not being crushed” and not necessarily, going somewhere.

This way of thinking is reflected in how Jaar approaches art, and life, perfectly captured in Edinburgh’s art festival piece. This notion of going on – regardless of how you feel, not getting crushed.

Ahmed reminds us furthermore of all the things complaining could mean without getting through, without reaching justice. Without hoping to reach justice since you know well that the system is broken. Yet, “Complaints can stir things up. Complaints can stir up other complaints” Ahmed avoids using the verb “fail”. the complainer never fails. Whenever they give up, wherever they stop, wherever they are stopped, frustrated by scratching the surface, they have left something behind. Even leaving is a statement by itself. “An empty space is still a thing, even if it’s defined by absence.” *

You can’t fail when you are not seeking to win. Complaining could be about paving a path. Going on because “The more a path is used, the more a path is used.” Ahmed said in a lecture on Complaint as Diversity Work. Paving a path, gathering resources, creating a record, forming a collective, filling a cabinet, witnessing a burial. Watching complaints get buried, a piece of you, a part of your history, being buried. Ahmed mentions a student using the sinister metaphor of a complaint graveyard. A burial could be the end of it. Ahmed does come back to this metaphor as she closes the last chapter, this time, however, she reassures, something will rise from those graves.

The complaints that disappeared behind the doors, the ones that became a burden on our backs, the ones that were never made, they all might make it to the graveyard, make it less lonely. Make the ghosts less lonely. Make the graveyard much harder to manage. That’s the goal of forming a complaint collective, becoming harder to manage. And if, when, the ghosts come back to haunt the institutions, they won’t be stopped by doors and walls. Ahmed writes: “I think of little ghosts and I hear little birds, ‘little birds scratching away at something.’”

I Can’t Go On. I’ll Go On.

Alfredo Jaar, “Art provocateur Alfredo Jaar: ‘I want to change the world. I fail all the time’,” interview by Dominic Rushe, Guardian, August 1, 2019, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/aug/01/alfredo-jaar-artist-interview-change-the-world-pinochet-chile-edinburgh.

Alfredo Jaar, “Photo realism – an interview with Alfredo Jaar,” interview by Robert Barry, Apollo, July 26, 2020, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.apollo-magazine.com/photo-realism-an-interview-with-alfredo-jaar.

Alfredo Jaar, “Alfredo Jaar – interview: ‘You can talk about violence without humiliating the victim’,” interview by Joe Lloyd, Studio International, December 19 2019, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/alfredo-jaar-you-can-talk-about-violence-without-humiliating-the-victim.

“Book Review – Art & Activism in the Age of Globalization,” We Make Money Not Art, December 27, 2011, accessed January 25, 2022, https://we-make-money-not-art.com/art_activism_in_the_age_of_glo.

Alfredo Jaar, “THE AESTHETICS OF WITNESSING: A CONVERSATION WITH ALFREDO JAAR’,” interview by Patricia C Philips, Public Art, Fall 2015, accessed January 25, 2022, https://publicart.ie/en/main/thinking/writing/writing/view//a42117773b66aedacec0bba127955203/?tx_pawritings_uid=43.

Sara Ahmed, Complaint! (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021)

Sara Ahmed, “Complaint as Diversity Work,” uploaded March 2016, video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQ_1kFwkfVE&ab_channel=CRASSHCambridge.

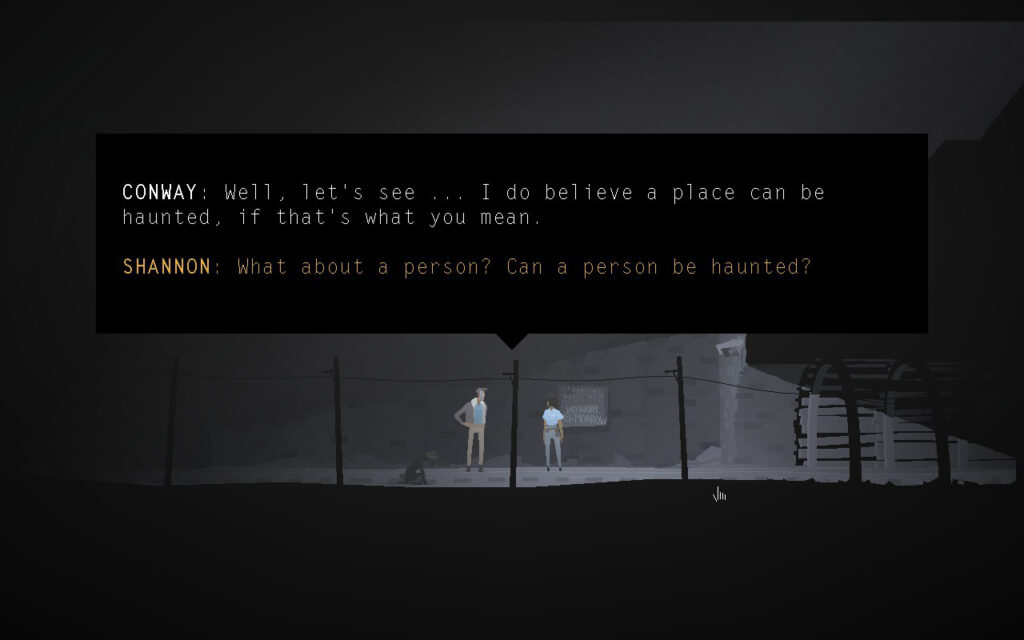

* This one might feel like an out of place source to cite. The indie game developer Scott Benson worte the said line in a article about the video game Kentucky Route Zero. KR0 deals with matters such as capitalism, debt, loss, and death. Benson wrote in another section: “Kentucky Route Zero has, among other things, always been about what happens after disaster. Those who are gone aren’t restored, not bodily anyway. But they’re here.” Reading complaint! made me imagine a video game, with the protagonist running through an infinite collider with endless doors. I think it’s the presence of the topic of survival that makes me keep coming back to a video game idea when reading the book, and to connect the concept with video games. “Scott Benson’s Top 10 Games of 2020” Giant Bomb News, Giant Bomb, January 21, 2021, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.giantbomb.com/articles/scott-bensons-top-10-games-of-2020/1100-6094.

KR0 is a beautiful text-heavy game, like playing rhrough a novel. Highly recommended.

“Blanking can be an action performed in relation to written and spoken complaints. You can be blanked in person. A senior academic made a complaint about bullying from her head of department. Her head of department had told her he was recording their conversation during the conversation. In a subsequent meeting with administrators, she asked about this recording: “They just stared at me, they didn’t answer, they did not speak, which I just found quite extraordinary.” A blank stare can be how you are received; you say something, and they say nothing back. This is not ordinarily what happens in conversations during meetings (“I found it quite extraordinary”). She is turned into a spectacle by not being heard (“they just stared at me”). By not saying something in response to what she says, it is as if she has not said anything. When you say something, it needs to be acknowledged as having been said. This is what blanking can be doing: when someone says something, you can stop what they say from being said by acting as if they did not say it.”

Complaint!

Sara Ahmed

One student said of her complaint, “It just gets shoved in the box.” Another student said, “I feel like my complaint has gone into the complaint graveyard”… Doing things in the proper way, doing what you are supposed to do, can lead, does lead, to a burial. If a burial should not happen but does happen, then burials might not appear to have happened; a burial can disappear along with what has been buried. 1

Growing up as a bookworm, I sense a subtle tinge of shame admitting that I have only read a handful of books during the past few years. In my defence, the past few years were anything but normal. They seem like a never-ending train of tragedies, always keeping you on edge, wondering if you should perish the moment because what is yet to come is going to be even worse. Years of therapy were undone in a matter of months, and my already dwindling attention span got absolutely annihilated.

Choosing to take part in a course where the main task is read the damn book does not seem like the wisest decision. But I wanted to push myself, and having been familiar with Ahmed’s work, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to immerse myself in the new book, finding different, personal, and artistic ways to approach it.

And I’m gonna be honest – I have become a slow reader. But to my surprise, Complaint has been a rather easy read. Now, it might be condescending to describe a book by a scholar who’s been a professor, an academic worker, and a diversity worker as an easy read. Nothing this woman has done in her life could be spoken of in the same breath as anything easy . And a book that deals with such sensitive, important topics such as discrimination and harassment, and all the ways you could fail if you seek justice – How could it be easy to read?

Yet part of what makes Ahmed such an important feminist scholar is her ability to write in a way which is both accessible and cautiously intimate. Her aim is not to write specifically for people with a similar background or knowledge, at least not in this specific book, and not in, say, Living a Feminist Life. What we have here is not a textbook, you don’t have to put a bunch of reference books next to you to get what is discussed, all you need is being willing to become a feminist ear, as Ahmed herself.

Complaint?! Is thereby an accessible book in both the way that it is written and the way it is structured. Before reading the book I listened to a few of Ahmed’s talks about her research throughout the writing process and the experience of reading the result is very much like listening to her. Complaint?! is an unapologetically emotional book. Is a collection of testimonies, as Ahmed likes to call them, yet not a simple report. If there’s one thing I have learned from this book is that there are already enough reports on complaints in this world – somewhere in a cabinet probably. She plays with words carefully, not too much to be a distraction but just enough to make sure that she still has your attention, which makes the text – if I dare judge – poetic and very human.

If a complaint is made to create more time and more room, a complaint can take time and leave you with even less room. The less time you have, the less room you have, the more conscious you become of who is given time, who is given room. 2

Using metaphors – sinister ones: doors, burials, bodies that have stopped functioning… -and repetitions, Ahmed makes sure that a common language, a common understanding is being shaped gradually between her and the readers – who may or may not have been in the situations described in the book, or may or may not have privileges that would make them unlikely to ever experience them. And may or may not have the attention span of a squirrel after having spent what seems like a lifetime in isolation and a constant state of fear. And it’s amazing how empowering this sense of having achieved a common language is. How relieved you could feel when you hear what you could have not expressed in someone else’s words. Even if the relief is followed by a vague sense of helplessness, it is still something. It’s like putting feelings in words makes them justified, gives them a face, their very own identity. And it might make them scarier at the beginning – “words can never hurt me” says a liar or a fool – but that’s a start.

I think.

How do you pull yourself together to share an experience if an experience is of breaking apart? 3

An animated 3d model of a compliant as it was drawn by Ahmed in the book. It shows how the process is not in and out, but round and round and round.

You could lose your way, it swallows you.

1. The First Gathering

Our first session was an intimate one. Considering the fact that it’s been a good while since I actually sat with people who were not my close friends and family or hiding a good half of their face behind a mask, it was even more joyful.

The organisation part and introductions aside, we talked about the book cover, which is a photograph of the installation “Double-Doors II, A+B”, 2006/2007 by Rachel Whiteread. We talked about doors as façades – implying that there is a way forward, a way out. Yet all is waiting for you behind them is a wall, or better yet, another door. Leading to another door. Hoping, waiting for you to give up, to turn around. To stop trying.

It reminds me of a Polygon article I read a good while ago about the video game Bioshock: Infinite. I can’t remember much of the article – but I remember that somewhere I stumbled upon this John Scalzi quote: „Being a straight white man is playing life at the lowest difficulty setting there is.” I liked this quote, I still do, it sounds smart. Difficulty settings of life as the difficulty setting of a video game. I’d argue that the same applies to our topic, winning the game of getting through the doors. Doors will be bigger, taller, more intimidating the further you get from being an able bodied cis straight white man. And you’ll be carrying more than your own weight (and your paperwork) with you. All the things that you had to overcome, to prove, as a woman wanting to exist anywhere other than under your own roof, inside your own walls, behind a door. The very first door separating you from the world outside, from fresh air.

This is a concept that I know too well as a woman coming from the middle east (which is not a good start to anything) and from a highly religious, patriarchal and misogynistic society. The first thing you learn as a little girl in my country is that the world outside is not safe. The streets, oh specially the streets at night but streets in general – metro underpasses, university, workplace, your boss’s office – definitely not safe. Your boyfriend’s home? God no. ANYONE’S HOME – say, a co-worker you have to shortly meet to hand them some documents, an artist who is holding classes in their home – oh, dear, you’re so looking for trouble if you go there.

Just being in these places means you deserve whatever happens to you. That’s what we learn. Some hear it from others, worried moms, super-worried grandparents. Or you read someone’s experience on the internet. Then another one. then another. You hear it from a friend of a friend who had to run away from a driving car catcalling her and asking help from a police officer, only to be asked why she’s out so late at night looking like this. Your friend gets abused by her boss who had asked her to stop by his place to grab some files. Your friend is not going to tell anyone. No going to file a complaint. She knows too well where that door is going to lead. A few other doors, surly, to get her all warmed up, and a pretty good amount of victim blaming. Oh, and losing a job.

She learnt it as a little girl. And, she knows, as I do, and all the women in my country – you are not safe outside. So, anything that happens to you after you close your home’s door behind you is your own fault. You were asking for it. You had it coming.

And well, what if a woman is assaulted inside her own house? Glad you asked: what happens behind closed doors stays behind closed doors. Private family matters, right? People argue. Husbands beat up their wives, fathers cut their daughters’ throats, brothers lock their sisters inside1. Such is life.

Thinking of a door as something which is separating your (if you’re lucky) safe space from the world outside led me to another interpretation of the picture of the doors without locks, without handles: you can’t keep anyone out. Assault – be it sexual, physical or verbal – is indeed nothing but an invasion of a personal space. A door without a lock can’t keep anyone outside, it can’t keep you safe.

2. The Book Launch

The online book launch took place exactly after our first session. I missed my bus and had to walk an unpleasantly long distance in the dark, while listening to Sara Ahmed and other women who had one way or another contributed to the book. Some of the women whose “testimonies’’, as Ahmed calls them, were used in the book came to word, and I was humbled by their courage and inspired by their strength to show where it hurts, to show vulnerability. I imagine every time you retell a story of experiencing abuse you are reliving it, opening the wounds again and again. Questioning your actions and doubting if you did something wrong, if you – typical in where I come from, as I mentioned – had it coming. I found myself envying those women – which does not sound right. But later as I talked about the event with a friend – also from my country – she said she felt it too. A sudden burst of loneliness hit us, as we realised how much we want to hear the same discourse in our mother language. How out of reach it still appears and how high the price of that could be.

Which brings me to another powerful aspect of the event, and the book, and the whole concept of a „feminist collective”: we are, in fact, not alone. Now, it doesn’t magically take the pain and the frustration away. But there is something empowering and comforting in knowing that. And the more people join the feminist collective the more powerful we are. We have even experienced it with Iran’s meto movement too, which has gained momentum in recent years. Women started talking, complaining, out loud, without censoring themselves, and about men, which is as horrifying as a woman can get – in the eyes of the abusers and their apologists. Big names were outed by the women who suffered harassment, especially in the art field2, and then many others got the courage to talk about past or ongoing traumas caused by co-workers, bosses, professors, friends, and family members.

I had all these in my mind, listening to the bittersweet event. And that’s when I heard yet another interpretation of doors from one of the participants, my favourite one: doors are not always there to frustrate and disappoint, she believes. Sometimes you open a door and there’s a whole feminist collective waiting for you behind it.

Growing, and empowering.