note: to simplify the formatting I have just simply put all the sources at the end of the text. For the detailed citation check out the file on Moodle or leave a comment.

Introducing the artist and the chosen artworks

“With my will, I have to be optimistic. If not, I would just kill myself.” says the Chilean-born and New York based architect, photographer, and filmmaker Alfredo Jaar during an interview with the Guardian, smiling playfully. It made me laugh out loud, not with joy, but relief. I joke about killing myself all the time – well, not all the time. But enough to make my friends uncomfortable – and I always have to explain that I won’t do it, I’m not planning to end my life. Not only because – Jaar quotes the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran in that interview – “It is not worth the bother of killing yourself, since you always kill yourself too late.” but also because I, too, have this will of going on. A blessing and a curse.

Jaar thinks of himself as “an architect who makes art”, and rightly so, given that he graduated from his architecture with a poem. He aims to raise awareness and to create empathy, to make us look at what we do not want to see, don’t have the heart for it, maybe – but not at the cost of trivializing suffering or humiliating the victims, without relying on cheap thrills and easy provocations.

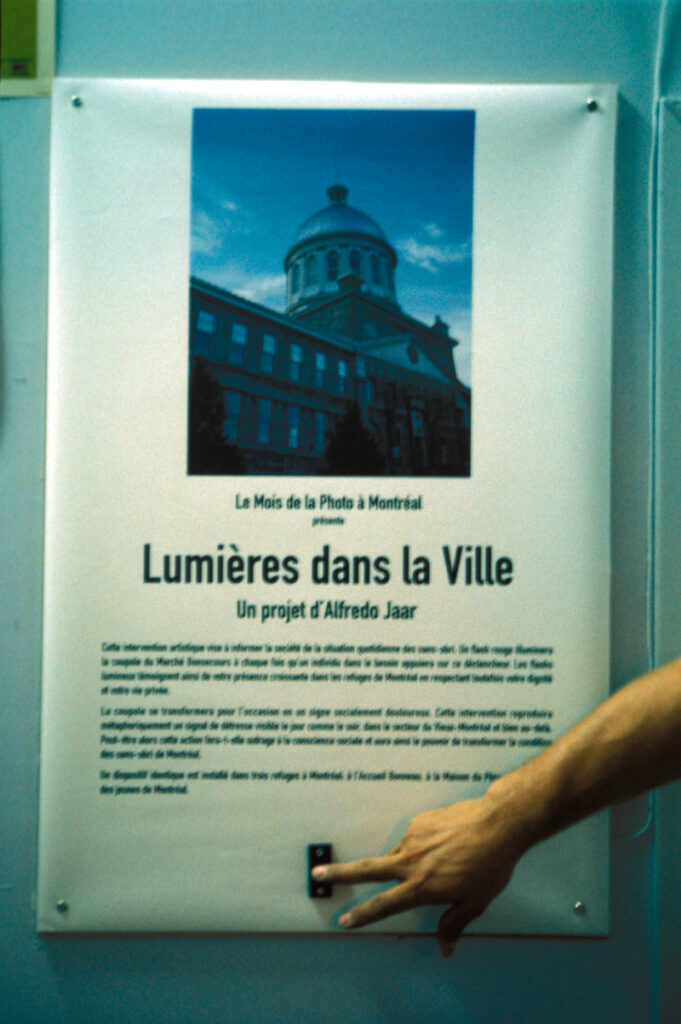

An example of this would be the project Lights in the City (1999) – a project designed to draw attention to the burgeoning issue of homelessness in Montreal.

The artist installed red light on the Copula of the Marche Bonsecours, a landmark monument in the center of Montreal. The lights were connected to homeless shelters located 500 yards from the building. When a homeless person entered one of the shelters, they could press the button that would make the top of the building glow red.

The historic landmark had burnt around five times before this project came to fruition. The glowing red light could therefore be interpreted as yet another fire, Jaar says. But the main message was far more important. Jaar wanted the building to become a “permanent monument of shame” We come to ignore photos and video reportages, at some point, eventually. As we are surrounded by too many of them. Too much suffering you’d become numb, and distracted by the next photo advertising the dream vacation.. He does not want to be a part of that.

You see an image of poverty here, you see another tragedy there. You see a couple of headlines and then see you see advertisements for a vacation for Hawaii. And so these images of pain, of suffering, are drowning in a sea of consumption.

For this reason, and also because he did not want to expose the homeless people through photography, the route was taken to make a historical building in one of the richest cities of the world the very symbol of the issue of homelessness. One might become indifferent to the images of pain, of suffering, it is, however, much harder to ignore that each time the building lights up with that bright, intimidating red, a homeless person has pressed the button. It was Jaar’s way to move the city by the sheer number of the people who did not have a place to call home – without humiliating and dehumanizing them.

The project was canceled six weeks later by the mayor. “With these projects you change so little” says Jaar. Speaking one of my dark thoughts every time I find myself admiring an installation, a performance, an artistic idea aiming to bring about positive change – They change so little.

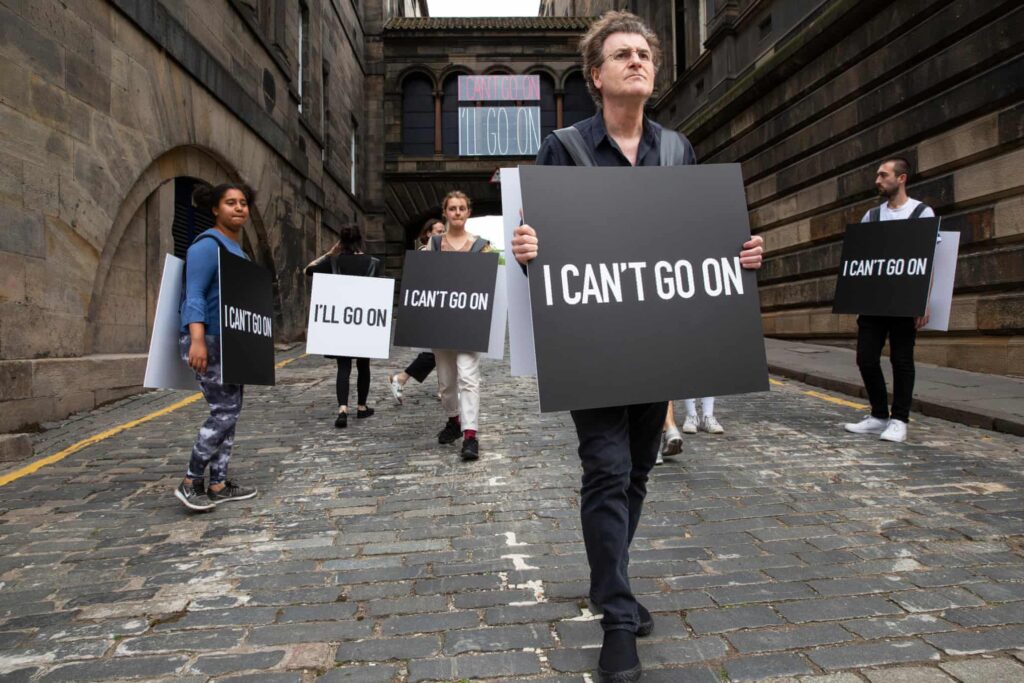

Yet Jaar, as mentioned in the beginning, has to be optimistic. A message conveyed with his public artwork at Edinburgh art festival 2019, I Can’t Go On, I Go On. Taken from the ending words of Samuel Beckett’s The Unnameable. During the festival performers would wear sandwich boards with I Can’t Go On on their chests, I’ll Go On on their backs.

“It’s about our incapacity to change this reality, even though I keep going, I keep trying. Because this is the only thing I know,” Jaar says. His optimism also manifests itself in his decision to dedicate a third of his time to teaching. He believes in the younger generation. “Perhaps someone who sees his Edinburgh piece this week will be inspired to make their own work. Perhaps they will offer us a new vision that can help us navigate the darkness.”

Relevance to Sara Ahmed: Complaint!

A Complaint, Ahmed writes, “raises the blind.”, which parallels with how Jaar uses his art to draw the attention of the public to the matters left undiscussed or ignored. The homeless shelter next to the Capula in Montreal was “invisible, just like the homeless were invisible… They were overlooked, as a garbage can or a lamppost is ignored” The Lights in the City project gave them back the humanity, made people recognize their existence, even through a smile. The issue was also raised in the press. “We gave them a brief, hopeful moment when they regained their humanity,” says Jaar, adding to the statement that he and his team wanted the Capula to become a permanent monument of shame. “Other shelters wanted to join us and get connected” implying that originally, there was a long term plan. Each night, the historic building was to burn red, burning again and again and again, reminding the city how it has failed to protect its most vulnerable. The homeless were the living, breathing proof of this failure and their invisibility the result of the most simple coping mechanism known to man: Avoidance.

Violence is often dealt with by not being faced. It is then as if the complaint brings the violence into existence, forcing it to be faced. Perhaps this is why complaints are often heard as forceful. For those who received the complaint, who heard the sounds she made, it was the complaint that alerted them to violence. A complaint is how violence is revealed; a complaint raises the blind.

The mayor, I assume, dealt with the problem by dealing with what was raising the problem. “When you expose a problem you pose a problem.” The homeless went back to their state of invisibility, ignored as a garbage can or a lamppost, and people went back to ignoring them, living their day-to-day life, the burden of guilt upon seeing the Capula burning bright off their shoulders. I do not blame the people, of course. Dealing with the issue of homelessness is a problem beyond individual responsibility. Yet with the attention of the public and the press being withdrawn, there was so little left to impose a degree of moral pressure on the authorities. “I fail all the time.” Jaar told the Guardian. “You change so little.”

Having jaar’s intention in mind, one might argue that the project “failed” in ways more than one: he recalls running into some drunken men one night, wandering in the streets and cheering with joy as the red lights in the capula brightened. It’s hard to imagine someone reading Complaint! or listening to one of Ahmend’s speeches and missing her point, yet conveying a message through art always runs the risk of misinterpretation. Jaar’s Lights in the City was no expectation. “You cannot predict what will happen when your work is in the public space.” says Jaar.

Demonstrating a horrible truth through art might leave you with something that is, in the eye of the beholder, solely something beautiful to look at. However, I’d dare say that more people would be willing to visit a “cool performance art”, than reading a text book on sexual assault. But only one of them in guaranteed to convey the message the creator is intending to.

“Many of the stories I have collected in this book seem to be stories of working very hard not to get very far.” Ahmed admits this vague hopelessness near the end of the book Complaint! This cold fear that would turn your stomach. We’re changing so little. But she proceeds to add: “a complaint is a way of not being crushed” and not necessarily, going somewhere.

This way of thinking is reflected in how Jaar approaches art, and life, perfectly captured in Edinburgh’s art festival piece. This notion of going on – regardless of how you feel, not getting crushed.

Ahmed reminds us furthermore of all the things complaining could mean without getting through, without reaching justice. Without hoping to reach justice since you know well that the system is broken. Yet, “Complaints can stir things up. Complaints can stir up other complaints” Ahmed avoids using the verb “fail”. the complainer never fails. Whenever they give up, wherever they stop, wherever they are stopped, frustrated by scratching the surface, they have left something behind. Even leaving is a statement by itself. “An empty space is still a thing, even if it’s defined by absence.” *

You can’t fail when you are not seeking to win. Complaining could be about paving a path. Going on because “The more a path is used, the more a path is used.” Ahmed said in a lecture on Complaint as Diversity Work. Paving a path, gathering resources, creating a record, forming a collective, filling a cabinet, witnessing a burial. Watching complaints get buried, a piece of you, a part of your history, being buried. Ahmed mentions a student using the sinister metaphor of a complaint graveyard. A burial could be the end of it. Ahmed does come back to this metaphor as she closes the last chapter, this time, however, she reassures, something will rise from those graves.

The complaints that disappeared behind the doors, the ones that became a burden on our backs, the ones that were never made, they all might make it to the graveyard, make it less lonely. Make the ghosts less lonely. Make the graveyard much harder to manage. That’s the goal of forming a complaint collective, becoming harder to manage. And if, when, the ghosts come back to haunt the institutions, they won’t be stopped by doors and walls. Ahmed writes: “I think of little ghosts and I hear little birds, ‘little birds scratching away at something.’”

I Can’t Go On. I’ll Go On.

Alfredo Jaar, “Art provocateur Alfredo Jaar: ‘I want to change the world. I fail all the time’,” interview by Dominic Rushe, Guardian, August 1, 2019, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/aug/01/alfredo-jaar-artist-interview-change-the-world-pinochet-chile-edinburgh.

Alfredo Jaar, “Photo realism – an interview with Alfredo Jaar,” interview by Robert Barry, Apollo, July 26, 2020, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.apollo-magazine.com/photo-realism-an-interview-with-alfredo-jaar.

Alfredo Jaar, “Alfredo Jaar – interview: ‘You can talk about violence without humiliating the victim’,” interview by Joe Lloyd, Studio International, December 19 2019, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/alfredo-jaar-you-can-talk-about-violence-without-humiliating-the-victim.

“Book Review – Art & Activism in the Age of Globalization,” We Make Money Not Art, December 27, 2011, accessed January 25, 2022, https://we-make-money-not-art.com/art_activism_in_the_age_of_glo.

Alfredo Jaar, “THE AESTHETICS OF WITNESSING: A CONVERSATION WITH ALFREDO JAAR’,” interview by Patricia C Philips, Public Art, Fall 2015, accessed January 25, 2022, https://publicart.ie/en/main/thinking/writing/writing/view//a42117773b66aedacec0bba127955203/?tx_pawritings_uid=43.

Sara Ahmed, Complaint! (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021)

Sara Ahmed, “Complaint as Diversity Work,” uploaded March 2016, video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQ_1kFwkfVE&ab_channel=CRASSHCambridge.

* This one might feel like an out of place source to cite. The indie game developer Scott Benson worte the said line in a article about the video game Kentucky Route Zero. KR0 deals with matters such as capitalism, debt, loss, and death. Benson wrote in another section: “Kentucky Route Zero has, among other things, always been about what happens after disaster. Those who are gone aren’t restored, not bodily anyway. But they’re here.” Reading complaint! made me imagine a video game, with the protagonist running through an infinite collider with endless doors. I think it’s the presence of the topic of survival that makes me keep coming back to a video game idea when reading the book, and to connect the concept with video games. “Scott Benson’s Top 10 Games of 2020” Giant Bomb News, Giant Bomb, January 21, 2021, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.giantbomb.com/articles/scott-bensons-top-10-games-of-2020/1100-6094.

KR0 is a beautiful text-heavy game, like playing rhrough a novel. Highly recommended.